Lewis and Clark Explorations of the Missouri River

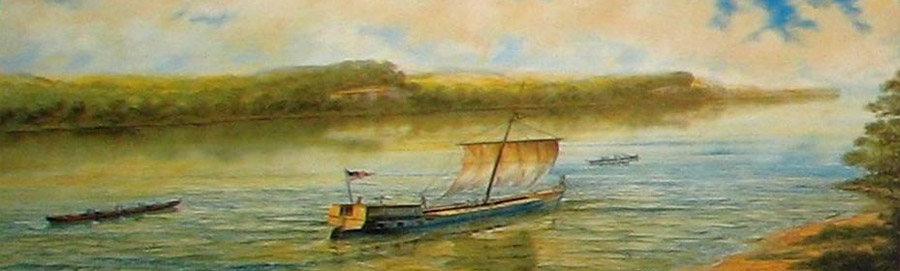

Traveling by keelboat and dugout canoes, Lewis and Clark and their party of soldiers and scouts explored, mapped and described in detail the entire length of the Missouri River as part of their exploration of the Louisiana Purchase. At the time, the Missouri River functioned naturally, without man-made influences such as dams or channelization.

Lewis and Clark marveled at the river’s abundant wildlife and natural landscapes, and wrote descriptively about the river’s challenges to their mission. Soon after Lewis and Clark concluded their exploratory expedition, an array of commercial interests endeavored to take advantage of the river basin’s resources. Fur traders, gold miners, buffalo hunters and other fortune seekers were greatly aided by the river’s navigational opportunities.

Excerpts from the journals of William Clark provide a written description of the natural Missouri River, a place that no longer exists. These journal entries were written in late September 1804, when the expedition traveled through what is now the Oahe dam and reservoir area in present-day South Dakota. Warning: Spelling and grammatical mistakes abound.

Missouri River profile

The Missouri is approximately 2,340 miles long, making it the longest river in North America. The river drains a vast watershed region stretching from its source near the northern Rocky Mountains through plains, prairies, and the modern, western corn belt that includes 529,000 square miles, and includes all or parts of ten states and two Canadian provinces. Of American rivers, only the Mississippi River drains a larger area. The natural Missouri’s broad and fertile floodplain tempts developers but widely varying flows including regular flooding make it a problematic river for transportation, riverside settlement, and other commercial interests. The river’s natural character included a broad channel, and a shoreline ranging from steep soil banks to dunes and expansive sandy beaches. Islands were not uncommon, and thick woods with many different tree species were found along the main channel and in the floodplain. Meadows, marshes, and brushy backwaters provided additional types of habitat that altogether made Missouri’s riparian ecosystem the most productive on the Great Plains. After reviewing the prodigious variety and numbers of wildlife found along the river one author described the pre-dammed and pre-channelized Missouri as being the “Serengeti of North America.” Indeed, there were few other places on earth possessing such a concentration and variety of wildlife as the natural Missouri River and its floodplain.